WHEN MY FIRST book came out, its publisher had a functional and routine strategy for launching. Milkweed Editions would

collect blurbs.

send tons of review copies to editors and reviewers.

try to make contact with someone at The New York Times Review of Books.

organize a book tour of cities with well-known independent bookstores.

make repeated calls to publicity contacts in those cities.

A Different Approach

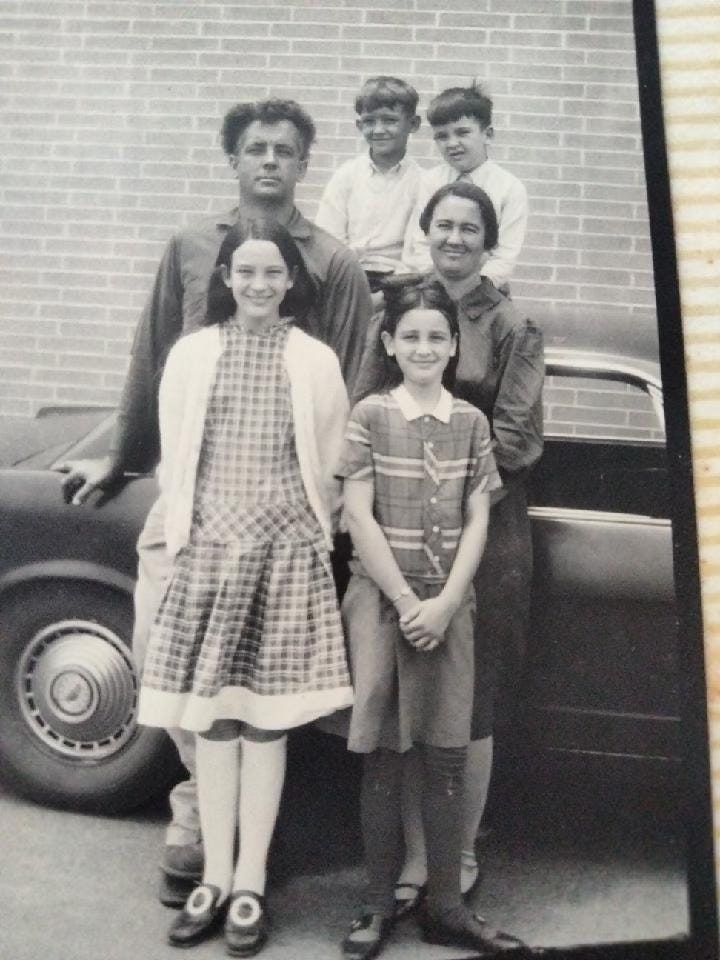

Here’s what my dad did.

As soon as he got his hands on a Milkweed catalog, he headed to town. He visited the mayor, clerk of court, presidents of the three banks, librarians, tellers, secretaries, and cashiers. Most of these people he knew from a lifetime spent in one place.

For most of these people, spending 20 bucks on a book was not insignificant. The average income for Baxley at the time was $24K.

“Mr. James Kilgo has read the book,” my dad would tell folks. “He’s a professor up in Athens. He called the book a ‘treasure’ of knowledge.”

“You don’t have to pay now,” he told his customers. “Wait until the books arrive.”

What Happened

My father pre-sold 200 books.

Over the course of the first year, three print-runs of hardbacks totaled 10,000 copies. My father sold 1,200 of these—12 percent of the total. I know this for a fact because one evening he and I added up his invoices.

Of course, yes, the successes of a book can be attributed to a good publicist at a great publishing company.

But I don’t think my first book had a better publicist than my dad.

Franklin’s 7-Point Strategy

Before he died I asked my dad about his selling strategy, and the laid it out for me. I’m laying it out for you here for you, in case you have made a book and are trying to get it to the right people. Your people.

1. Believe in your product.

First, Daddy said, believe in your product. For him, the product was not simply a book. My father would not have wasted a minute trying to vend Gone with the Wind or Light in August.

What Franklin was selling was something anybody could buy—the dream of a son or daughter doing good. If this could happen to Frank Ray, out at the junkyard, it could happen to anybody. In our town he'd always been an underdog, a poor boy, a junk man, part of the Ray clan with its mental illness, the one sent off. He was selling pride. He was selling the fact that a backwater place had spawned a book.

2. Create a market.

Create a market, my father said. Create interest. Create curiosity. Create a sense of belonging.

Gossip raced through town. Townspeople were hearing they were in the book, and they wanted to check how they'd been represented. They wanted some things explained.

Franklin was selling membership to a club, composed of people who knew firsthand what was between the covers. One gentleman purchased a book for himself but his wife absconded with it. She would read the book in the evening, and when she left for work she’d take it with her. The man was dying to read it and couldn’t get it away from his wife. His solution was to buy another copy. He wanted to be in the club.

Daddy delivered a copy of the book to one man, Dewayne Yeomans, late in the afternoon at his place of business. Mr. Yeomans was single at the time, and instead of going home, he sat at his desk after closing time and began to read. He didn’t stop, he told me later, until he'd read the entire book, finally quitting his office in the wee hours of the morning.

For a salesman, these are hugely valuable stories. They create excitement, which is a market. My father used these stories to sell even more books.

Then my father began to roam beyond my hometown, going farther afield. The trunk of his car was jammed with boxes. Now when he peddled he took with him articles from newspapers, including The New York Times, laminated.

Often a few days before a reading my father would canvas a town, carrying with him a flyer I'd made, to drum up interest. He’d visit first the people he might know in the area, visit the venue where the reading was to be held, then visit whomever he found. He was on a mission to tell the world about this book.

All these are ways he created a market.

3. Create supporting products.

Franklin's third principle was to create supporting products. One afternoon I arrived to my parent's home, planning to drive with them to a reading in Waycross, an hour away. My mother was wearing a T-shirt with the cover of the book silkscreened on it. Above the cover was my name, and below, the words AUTHOR, ENVIRONMENTALIST, POET. T-shirts were $12.

On a drive to Darien to a book festival, my parents talked about getting a similar design printed on a magnetic panel for the vehicle.

4. Any book can turn into a silver bullet.

My father's fourth principal of selling is the most important. Any book sold could turn into a “silver bullet,” striking the heart of Oprah, or the editors of The New York Times Review of Books, or Reese Witherspoon, or the Georgia Writers Hall of Fame judges. No matter how “average” a buyer—how uneducated, how provincial, how homely—that person might open a door.

This theory harkened to the Biblical admonition, Beware how you treat strangers, that you might entertain angels unawares. Somebody from Podunk, Georgia might have an aunt who has a cousin who knows somebody who works at the The New Yorker or who teaches at Harvard.

There isn’t one silver bullet. There are many.

Any book might become one.

5. A purchase is not only a material item.

Fifth, remember that a purchase is an experience. A purchaser had the chance to interact with my very interesting father. Any time of day the phone might ring and my father might want me to drop everything and drive the seven miles from my grandmother's farmhouse, where I lived, to the junkyard. He had somebody who wanted to meet me. Other times, he brought visitors unannounced to my house. A box of books did not arrive without me signing it immediately. To him, my signature was gold.

6. Offer a money-back guarantee.

If anybody, for any reason, did not like the book, Franklin would accept it back and fully refund the person's money. He always offered this. I don't think it ever happened.

7. Tell everybody.

Franklin's last principle of book-selling was: like flies on sticky paper, nobody escapes. If people stopped at the junkyard to look for a Hudson side mirror, they didn’t leave until they had bought a copy of the book. They got the sales pitch first.

Once a man stopped at the junkyard to examine a vintage Studebaker. He left with a copy of Ecology, a book sale propped up by tales and news articles, T-shirts and car signs, a money-back guarantee. A week later, the man returned. He was the owner of a chain of breakfast restaurants and was opening one in town. He wanted to buy 25 copies of the book to distribute among his board of directors.

He’d been struck by a silver bullet.

When I Went Indie

WHEN I QUIT trying to publish in New York—when I became an author entrepreneur, which is very different from being an author—I realized quickly that the normal launching strategy wasn’t working. It works for very few people, in fact.

I quit blurbs. Praise from famous authors on back covers is impressive, but I don’t think that’s what sells books.

I quit sending out review copies.

There was no use to try making contact with the NYT Review of Books. No use at all.

A book tour supports indie bookstores—and I love that—but I’ll make more money if you buy my book straight from me, wherever you can find me. Most reliably that will be my website.

I quit begging for publicity. I use the tools I have—email list, mailing list, social media, advertising, events.

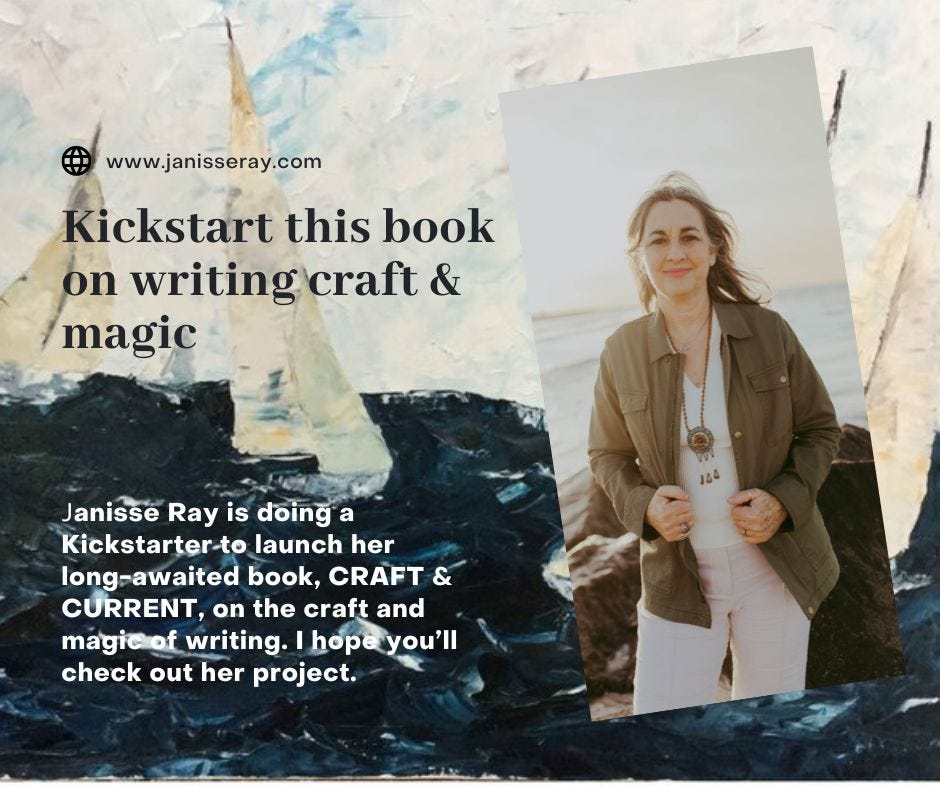

Kickstarter

Now I’m using Kickstarter too. It’s just another tool. I’m giving it a whirl, and if it doesn’t work, I’ll quit.

Yes

My dad’s strategy is old-fashioned. But right now I’m thinking old-fashioned is the way to go.

If You Want to Share It

Thanks to all who have already shared. I’m trying to keep a list of names, but I’m falling behind. Please know I’m grateful to you.

Old fashioned is good!

I love these tried and tried different ways stories to success. Thank you Janisse!