For thousands of years, changes in society happened glacially. Humans lived for millennia in relationship with the earth, learning how to better survive on it, and in relationship with their groups, learning how to make them work.

With the advent of industry, change itself sped up, until the world in 1900 was almost unrecognizable to a person born in 1800. The world of 2000 was inexplicable to a person born in 1900. The world I live in now is in many ways unrecognizable from the one in which I was born, in 1962.

We are living in a massive upheaval of culture (a cancel culture of its own). From seed-saving to corporate hybrid seed, or from a mule to a self-driving Tesla—cultural reorganization is happening fast.

The next new thing is here and gone. In two months you won’t even hear the word “Barbie.”

With the rise of television and then computers (both of them more or less during my lifetime) I have watched books become less relevant in the cultural landscape.

This could be a palatable turn of events were I not deep into a lifelong love affair with books—as a reader, a collector, and a writer. It also would be more palatable were not so many other things I love disappearing.

The contrarian philosopher and hospice reformer Stephen Jenkinson wrote about this in Come of Age: The Case for Elderhood in a Time of Trouble. Jenkinson’s nonconformist roots, like mine, are wedged in the counter-culture movement of the 60s, which for all its flaws produced stunning thinking and lasting cultural change.

In Come of Age, Jenkinson recounts walking the aisles of an airport bookstore before a long flight, looking for a book but finding nothing that interests him.

“Really, they’re not even bookstores. They are grottoes of grim fascination with technology, and they are selling gizmos that promise to enhance the reading experience but are clearly helping to make books—the paper kind, what they call now the bricks-and-mortar of the trade—a nostalgic memory. This is something that is happening in your lifetime.”

The gist is that books are becoming a nostalgic memory. I see this, and I know you see it.

Look at the bestseller lists—how many books had to sell to get you on the list in 1980 (a million) and how many have to sell now (12,000, I heard most recently).

Look at libraries—their focus on computer access.

Look at the library parking lot in my town—empty.

Look at the average number of minutes an American reads per day—20 minutes for most people, closer to 45 for people over 70.

Change is upon us writers, books becoming nostalgic memories. But listen, if you’re a writer you can’t focus on decline. You have to focus on the power of books—a power that story, however presented, will always wield.

What can we do about the decline of books?

We can keep reading, some every day.

We can take our children to the library.

We can read to kids, as parents or as volunteers.

We can read to each other.

We can visit the library ourselves.

We can construct and stock a Little Free Library.

We can attend readings.

We can maintain a personal library.

We can write the best books and stories possible, ones that make a reader not want to put them down. (I’ll be writing more about this.)

__________________________________________

Help me. Please fill in #10 in the Comments section. What else can we do about the decline of books?

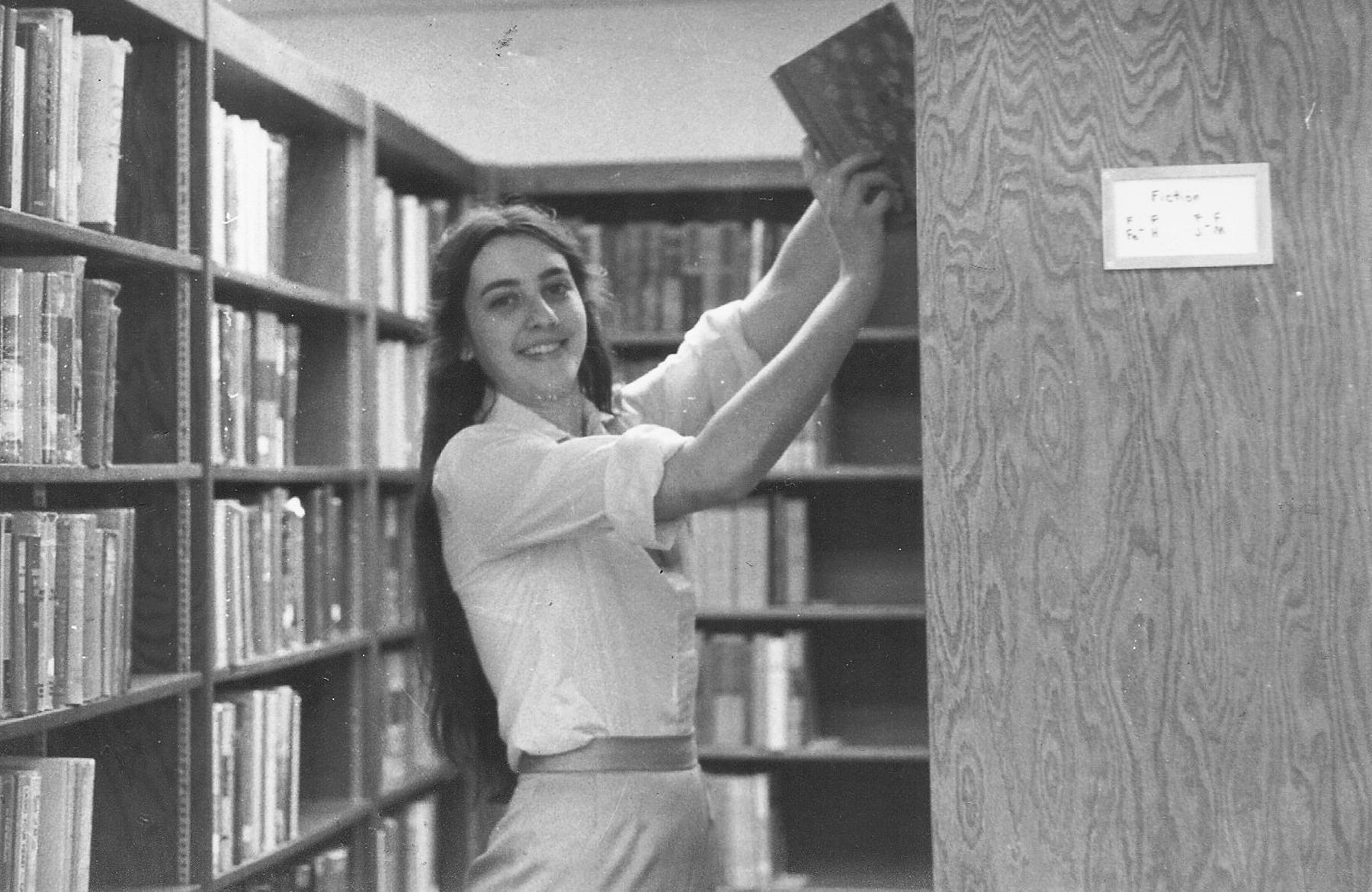

I started working at my local public library the summer I was 14, my first paying job. I learned the Dewey Decimal System before I learned to drive, which seems like a pretty good order of things.

We can gift and share with friends. An old friend from college and I have just started a book exchange by mail, complete with bookmarks.

Give books as gifts.